The Bishop of Truro will lead a service at cross built by Ukranian refugees escaping persecution after World War Two as country battles for freedom.

As the battle rages for Ukraine, people have been placing yellow and blue flowers on the monument in solidarity with its people. The monument was erected by the side of the road above the village by refugees fleeing persecution during the Second World War. The service will take place at 2pm. A vigil will also take place outside Truro Cathedral at 4.30pm this afternoon.

Sunday, 2pm the Bishop of Truro, the Rt Revd Philip Mounstephen will lead a service at the Ukrainian War Memorial in Mylor. All welcome.

— Diocese of Truro (@DioTruro) February 26, 2022

More information: https://t.co/BuPoWi1VxC

The War Memorial is on the side of the dead-end Road to Restronguet Barton, Mylor. @pmounstephen

People have been placing yellow and blue flowers on the monument at Mylor

The refugees were sheltered in a camp on the road to Restronguet Barton. Ukrainians among them who had worked in local farms, mines and gardens built a memorial when they left after the war.

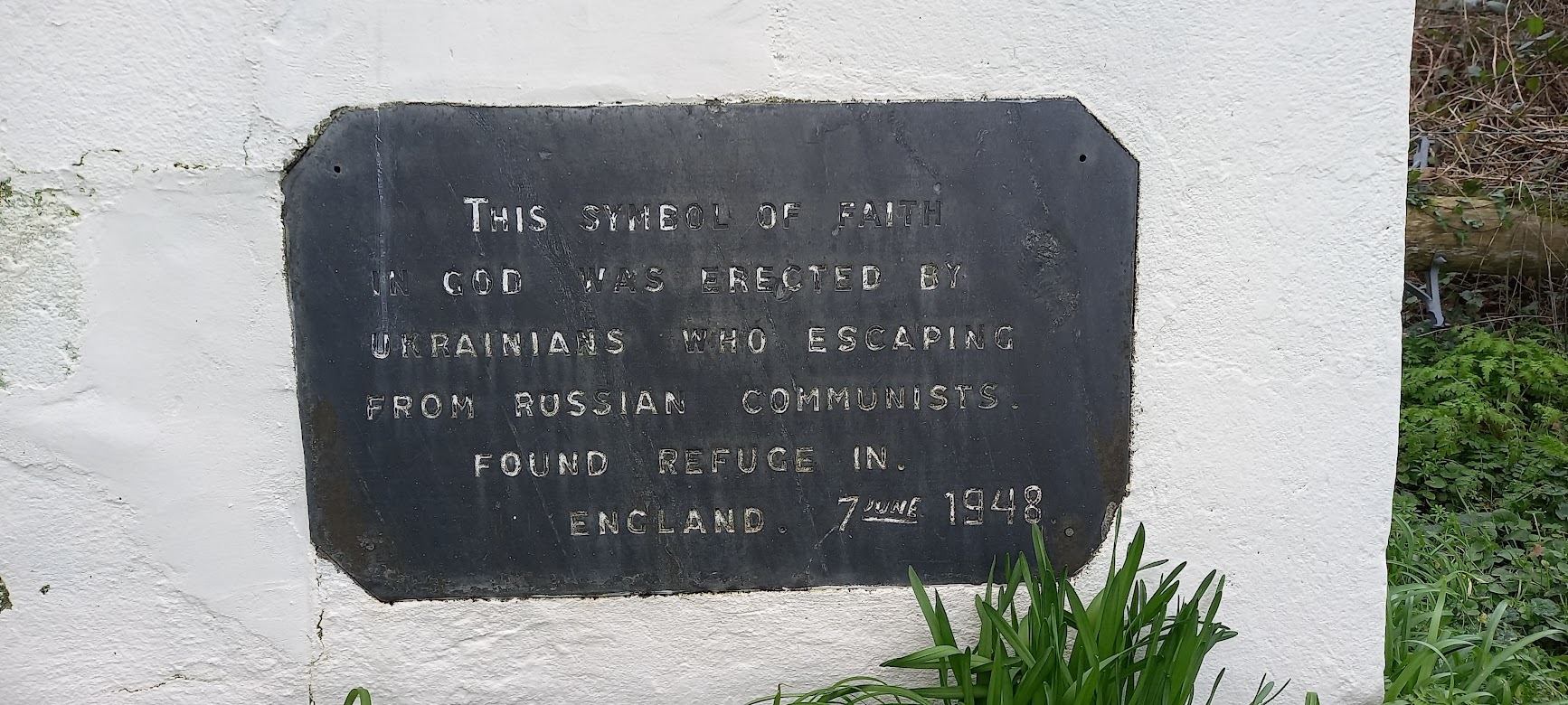

The cross is made of bricks and has another cross carved within it. On it is a plaque which reads 'This symbol of faith in God was erected by Ukrainians who, escaping from Russian Communists, found refuge in England. 7th June 1948'.

The Bishop of Truro will conduct a service at the monument at 2pm

This small monument was erected here in 1948 by a group of Ukrainians who had been living and working in the area in the post-war era.

The Ukrainian men and their families had a strong Catholic faith and would organise services in a make-shift chapel close to the hostel where they lived.

English priests would visit from Falmouth to offer pastoral care and lead worship.

Mylor Bridge's Mermaids WI have made a peace/friendship ribbon, which has been taken to the Ukrainian Monument, where people will be able to add their own yellow ribbon.

Other people in the village have been remembering the Ukranians who came to their village.

Local fisherman and parish councillor Chris Vinnicombe posted on Facebook his memories of one Ukranian who they dubbed 'Nick the Pole', even though he was from Ukraine.

"Nick the Pole everyone called him," said Mr Vinnicombe. "But he was Nicolas Muziack I think and he came from Ukraine after fleeing from Eastern Europe.

"He told me his story of how his family was captured by the Nazis, sent to a camp where they were split up, he said they checked his hands to see if had done physical work which he had, he went one way and survived in a slave labour camp, his other family members went the other way to the gas chambers, horrific.

"He said after working as a slave a few years later when the Russians counter attacked the Nazis fled the camp and he had to do the same, if anyone was caught working for the Nazis the Russians would shoot them.

"So he headed west and managed to find a ship which crossed the North Sea into England.

He came to Mylor and stayed in the refugee camp up what we locals call the gun sites, Restonguet Barton.

"There he met Brenda Ferris who was working on the land, they married and lived in Penryn, Nick passed away several years ago now, he came fishing with me for a couple years, he was a very kind man, he’d help anyone out and spent most of his time in his old black shed next the the post office in Mylor, tinkering with his boats and taking Brenda out for harbour cruises in the boat he built himself.

"I’m sure he’d be very sad and upset to see the events going on in his homeland right now."

READ NEXT:

Fires break out at Pizza takeaway and a restaurant as roads are closed

At a service of rededication held at the cross in 2008 the Falmouth Packet reported that amongst the crowd that attended were many of the grandchildren of those original Ukrainian families who found safety and welcome in Cornwall more than 70 years before.

The cross stands near a former prisoner of war camp were, in around 1947/48 the Ukrainian families moved into the empty buildings and stayed there for around 12 months.

The BBC reported at the time that the men found work on the local farms, in the mines and as gardeners, taking the place of the Cornish men that had never come home, and the women looked after the children and some took in sewing work.

As a devout Orthodox Christian community they built themselves a make-shift chapel on the site and local Catholic priests would visit to hold services for them. As time went on the refugee families gradually moved out of the camp, finding more permanent accommodation in the surrounding villages.

From people’s recollections of that time, despite some initial language barriers, the families integrated very well, soon becoming part of Mylor’s community. Their children and the children from the village all played together and in fact, many remained in Mylor for the rest of their lives, marrying local men and women.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel